Work in the lab integrates behavioral experiments with functional genetic and evolutionary genomics approaches to study the neural, genetic, and evolutionary mechanisms of behavioral trait variation in natural populations. Most of our previous and ongoing work has focused on stream fish models (i.e., Mexican tetras/cavefish and darters).

Ongoing projects fall within three areas of focus:

(1) Understanding how interspecific behavioral interactions (e.g., mating and fighting) influence the evolution of molecular and neural divergence between and within species.

(2) Identifying features of genomic architecture that facilitate the evolution of reproductive barriers (i.e., traits that prevent hybrids from forming or reproducing) in the face of gene flow.

(3) Leveraging instances of repeated phenotypic evolution to infer the molecular and neural basis of paternal care behavior and the predictability of the evolutionary process.

Click here to see a recording of Rachel’s talk on mechanisms and consequences of repeated evolution from the American Society of Naturalists’ Early Career Investigator Award Symposium at Evolution 2022.

Click here to see a recording of Rachel’s talk on the genomic basis of postzygotic isolation in darters from the 2020 SMBE Fitch Award Symposium.

Mechanisms of Repeated Evolution in Mexican Tetras

A major outstanding question in evolutionary biology is whether certain genes are more likely than others to contribute to adaptive change, and if so, what if any commonalities exist among those genes. Systems where repeated evolution has occurred offer a powerful means to investigate this question. I analyzed whole genome resequencing data from >250 individuals across multiple cave and surface fish lineages of the Mexican tetra to identify patterns of selection associated with cave adaption (e.g., loss of eyes, pigment, and sleep). I found that repeated evolution of cave-adapted phenotypes was driven by selection on standing genetic variation and novel mutations and genes repeatedly under selection are longer compared to the rest of the genome (Moran et al. 2023 – Nature Communications). This provides important empirical support for the hypothesis that genes with larger mutational targets are more likely to be the substrate of repeated adaptive evolution.

Additionally, this work uncovered a compelling example of convergent evolution in a core circadian clock gene across multiple cavefish lineages and burrowing mammals (naked mole rats and degus). Specifically, I observed that cry1a exhibits a nonsynonymous mutation, R263Q, located within the FAD binding pocket (Moran et al. 2022 – iScience). This mutation has evolved independently across deep evolutionary timescales in multiple lineages of subterranean vertebrates in a site that is otherwise highly conserved across plants and animals, suggesting a shared genetic mechanism underlying adaptive evolution of a behavioral trait (i.e., circadian disruption). Genomic analyses were paired with behavioral assays in naturally occurring cave x surface fish hybrids to functionally validate that genetic differences identified contribute to phenotypic differences in sleep.

The evolution of enhanced behavioral isolation in sympatry via male-driven reproductive and agonistic character displacement

Interspecific reproductive interactions are common when closely related species co-occur in sympatry. A growing body of work is revealing that such interactions can have large-scale ecological and evolutionary consequences. Our research investigates how mating and fighting between species influences trait evolution and speciation using darters, a highly diverse group of North American stream fishes.

Interspecific reproductive interactions are common when closely related species co-occur in sympatry. A growing body of work is revealing that such interactions can have large-scale ecological and evolutionary consequences. Our research investigates how mating and fighting between species influences trait evolution and speciation using darters, a highly diverse group of North American stream fishes.

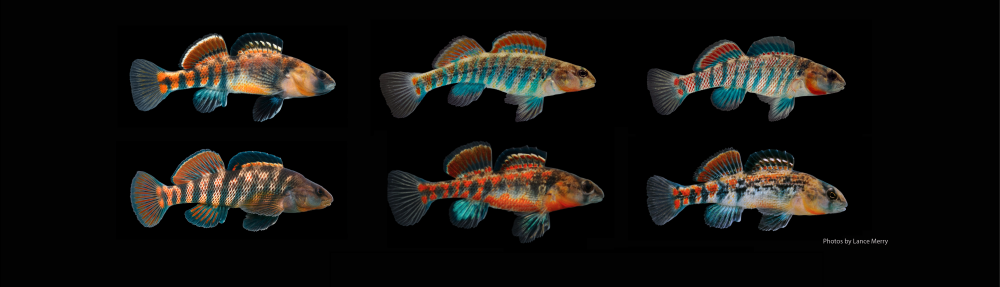

We study two wide-ranging groups of darters in the subgenus Oligocephalus: the orangethroat darter clade (Etheostoma:Ceasia) and the rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum). The orangethroat darter clade consists of 15 recently diverged allopatric species, 13 of which occur sympatrically with the more distantly related rainbow darter. Orangethroat and rainbow darters exhibit similar male nuptial coloration, ecology, and behavior, and they hybridize at low levels in nature. We use behavioral assays and comparative genomics to investigate which reproductive isolating barriers allow these species to co-occur with one another, and which factors have influenced the recent radiation of the orangethroat darter clade.

My previous work has demonstrated that selection to avoid maladaptive interspecific mating and fighting between orangethroat and rainbow darters likely plays a large role in driving speciation. When orangethroat and rainbow darters occur in sympatry, males strongly prefer to mate with conspecific over heterospecific females, and bias their aggression towards conspecific over heterospecific males. However, no such preferences exist when these species occur in allopatry with respect to one another. Thus, these species exhibit behavioral patterns consistent with reproductive character displacement in male mating preferences and agonistic character displacement in male fighting biases (Moran et al. 2017 – Evolution; Moran & Fuller 2018 – Proc Roy Soc B). Surprisingly, female orangethroat and rainbow darters do not appear to exert mating preferences for conspecific males, regardless of sympatry or allopatry with one another. This may be attributable to the high cost of choosiness females incur via egg over-ripening (Moran et al. 2018 – Journal of Fish Biology), and/or the possibility that male-male competition precludes female choice.

In addition to strong behavioral prezygotic barriers, we have found that postzygotic barriers also prevent gene flow between orangethroat and rainbow darters (Moran et al. 2018 – Ecology and Evolution). This suggests that reproductive character displacement in male mating preferences has evolved in response to the fitness consequences associated with hybridization (i.e. reinforcement).

Male F1 hybrids resulting from crosses between the orangethroat darter E. spectabile and the rainbow darter E. caeruleum exhibit color pattern intermediacy between both parental species (note caudal and anal fin coloration).

Secondary effects of reproductive and agonistic character displacement in sympatry can lead to divergence between allopatric lineages

Character displacement between two sympatric species results in a shift in species recognition traits (see figure below). This sometimes has the secondary effect of causing mismatches in species recognition traits between allopatric lineages (e.g. between populations within a species, or between recently diverged species within a clade). In this manner, reproductive and agonistic character displacement between sympatric orangethroat and rainbow darters appears to have also contributed to divergence between species within the orangethroat darter clade. I found that recently diverged species within the orangethroat clade exhibit surprisingly high levels of behavioral isolation from one another, but only when they occur in sympatry with rainbow darters (Moran et al. 2017 – Evolution; Moran & Fuller 2018 – Current Zoology). Thus, reproductive and agonistic character displacement between orangethroat and rainbow darters has two effects: (1) directly promoting increased reproductive isolation between orangethroat and rainbow darters in sympatry, and (2) indirectly leading to reproductive isolation between allopatric species within the orangethroat darter clade.

(A) Hypothetical ranges for Species 1 and Species 2. (B) Mating trait divergence is enhanced in sympatry between Species 1 and Species 2 due to reproductive character displacement (RCD), but populations of Species 2 respond to RCD in different phenotypic directions.

Mate choice copying in species with and without parental care

Individuals sometimes copy the mate choice of others to reduce the costs associated with choosing a mate. This phenomenon occurs in a variety of taxa, including birds, rats, deer, fish, insects, and humans, but has rarely been documented in both sexes within a species. Mate choice copying has been observed to occur more frequently in females than males. Traditionally, females have been thought to face a higher cost associated with choosing a mate compared to males because females invest more energy into producing larger gametes. However, in many species of fish, males invest heavily in reproduction by providing paternal care. Thus, investment in reproduction may be more equal between the sexes when males provide parental care. This has led to the prediction that when male parental care is present, both sexes should be more likely to mate choice copy.

For my Master’s thesis, I investigated mate choice copying in both sexes in two sympatric species of darters: Etheostoma flabellare, which exhibits paternal care, and Etheostoma zonale, which does not exhibit care. My objective was to determine whether the presence of mate choice copying is affected by differences in parental care between species while controlling to some extent for ecological and phylogenetic differences. Surprisingly, I found evidence of mate choice copying in both sexes of E. zonale (no parental care). I also found evidence of mate choice copying in male E. flabellare (male only parental care), but not in female E. flabellare (Moran et al. 2013). These results suggest that the presence of intense male-male competition in darters along with bright nuptial coloration in E. zonale and male care in E. flabellare may represent substantial costs to mating (Moran et al. 2014), leading to the observed pattern of mate choice copying in males of both species. Furthermore, in darter species in which males guard a nest and care for eggs, females prefer males that already have eggs in their nest (Moran 2012). Therefore, females in these species may gain more information about the quality of a male by directly observing his nest (and whether it contains eggs) than the presence of another female near his nest site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.